States Battling $130 Billion Obesity Crisis on Several Fronts

January 26, 2007

Contact: University Relations

Phone: 410.837.5739

With several states and cities taking positive steps to combat the nation's obesity epidemic, especially as it affects children, the University of Baltimore Obesity Initiative's third national assessment shows that quantifiable efforts are underway in various state legislatures—where a growing number of public-policy watchers believe that progress can be made to stop this costly and deadly trend.

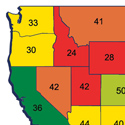

The Obesity Initiative's latest report card gives six states—California, Illinois, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Tennessee—an "A" for their legislative and public-policy work in the past year to control obesity in children. Only three states—California, New York and Tennessee—earned the same grade for their efforts across all populations. Still, the number of states taking steps to control the prevalence of overweight Americans is climbing rapidly, and the resulting attention in the media and the public is improving the odds that the epidemic—currently estimated by the Obesity Initiative as costing the United States $130 billion in direct medical costs each year (extrapolated from Centers for Disease Control estimates from 2000)—can be brought down to manageable levels.

Last year, for example, a band of states running east and west across the middle of the country were seen as doing little or nothing to combat obesity among their citizens. This year, that same region is showing across-the-board improvements, with Arkansas, Iowa, Oklahoma, Missouri, West Virginia and North and South Carolina all earning a "B" on the Obesity Initiative report card.

Kenneth R. Stanton, assistant professor of finance in the Merrick School of Business and co-founder and chair of the UB Obesity Initiative, said that efforts to stem this health care crisis are similar to those of the early era of the battle against smoking, when lawmakers, policy experts and opinion leaders began to make inroads against tobacco addiction in loosely connected ways.

"The progress reminds me of about 1991 or '92, in that certain messages about obesity are coming together and gaining traction," Stanton said. "You can look at New York City's decision to ban trans fats as a significant victory, in that it made national news and there was little outcry about it. In a lot of these actions, various populations—especially parents who worry about their children becoming obese—are saying that new, protective laws are actually overdue."

Zoltan Acs, professor emeritus of economics and entrepreneurship in the School of Business and co-founder of the Obesity Initiative, added that a state-based approach to combating obesity makes sense.

"We're seeing more of these laws coming out of the states, and some of them are quite effective. A federal solution would be much more difficult," Acs said. "Every state has a different mix of populations, a different outlook on diet and nutrition, and so a one-size-fits-all approach simply would not be feasible. I expect that, in the next three to five years, the obesity crisis will transition into something more easily handled by our health care system."

The two-part report card, "State Efforts to Control Obesity/State Efforts to Control Childhood Overweight Prevalence," was produced by the UB Obesity Initiative and the University of Baltimore's Schaefer Center for Public Policy. It assigned values to a wide range of legislative initiatives and policy shifts from this year, in categories including school-based nutrition standards, obesity programs and education, schools' emphasis on recess and physical education, access to treatment via health insurance and schoolchildren's access to vending machines in schools. Grades were given on both proposed and enacted legislation, and took into account the formation of state commissions and decisions to solicit research on obesity within a given state's population. Among the categories, research still lags behind other activities, while school recess programs have skyrocketed ahead.

"Recess and physical education in schools—this is the kind of easy, obvious thing that any state can undertake with little risk," Stanton said. "It's not seen as 'social engineering' to make sure that a third-grader has some playground and gym time to burn off calories and get some cardiovascular activity. Research on obesity is more complicated, but we believe it's part of the solution."

Ann Cotten, director of the Schaefer Center, said this year's report card represents an enhancement of the previous versions' depth and breadth, as reporting on obesity crisis initiatives becomes more regularized by the states.

"There has been more legislative activity at the state and local level," Cotten said. "Efforts such as the obesity scorecard help focus attention on the role of effective public policy as one piece of the obesity prevention puzzle."

In addition to writing and speaking on the topic, UB faculty members who are involved in the multidisciplinary Obesity Initiative have also provided direct guidance to legislators in Texas, North Carolina and Maryland. They have published in peer-reviewed journals ("The Infrastructure of Obesity," by Stanton and Acs, in Applied Health Economics and Health Policy); edited a forthcoming book, Obesity, Business and Public Policy; and presented at conferences and panel discussions. Many other activities are scheduled for 2007.

The report card, including a narrative and methodology, is available on the Obesity Initiative's Web site at http://www.ubalt.edu/experts/obesity.

The University of Baltimore is a member of the University System of Maryland and comprises the School of Law, the Yale Gordon College of Liberal Arts and the Merrick School of Business.